When Kent Glover enrolled at Hawaiʻi Pacific University (HPU), he already had his sights set on the Oceanic Institute. As a high school student in Alabama, Glover had been captivated by news that scientists in Hawaiʻi had successfully bred the Yellow tang—a landmark achievement in the world of ornamental aquaculture.

“At the time, that was a huge deal, and still is,” Glover said. “It completely changed what we know and how we do things now. I knew then that I had to be a part of this.”

His determination to make an impact on fisheries science carried Glover from HPU undergraduate to published researcher to now full-time Research Assistant at the Oceanic Institute, where he works at the intersection of marine conservation and aquaculture innovation.

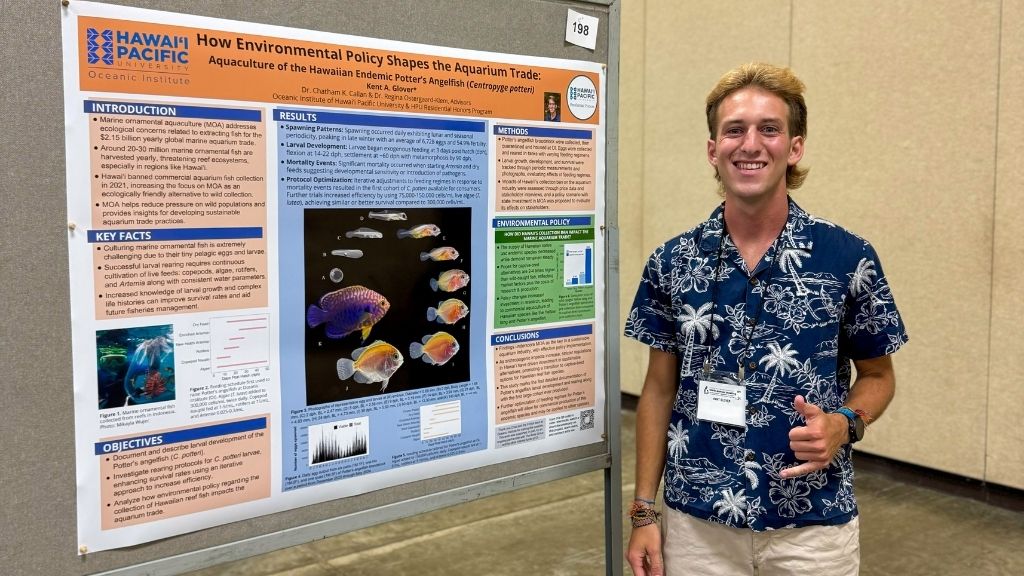

Glover’s recent co-authored paper, published in the Journal of the World of Aquaculture Society, details the successful rearing of the Potter’s angelfish (Centropyge potteri), a vibrant reef species found only in Hawaiian waters.

The study, which began as his undergraduate capstone project, represents the first replicated, species-specific protocol for raising Potter’s angelfish in captivity. “I was a volunteer intern at the Oceanic Institute, and we were raising species in captivity to offset collection from the reefs here,” he explained. “I was lucky to start the early phases of the research two years before my capstone.”

As a member of HPU’s Residential Honors Program, Glover took an interdisciplinary approach to his project, combining aquaculture science with environmental economics and policy, which coincided with a 2021 ban on collecting any fish off the reefs for the aquarium trade.

“I looked at the policy and politics surrounding the collection ban and how that influenced investment in our research,” he explained. “Because of the ban, we saw an influx of interest and want for this species because it’s endemic. It’s only found in Hawaiʻi. So, the only way to get this species out to aquariums worldwide is for us to raise it.”

Oceanic Institute Finfish Department Research Associate Katie Hiew and Research Assistant Kent Glover.

Glover and his fellow researchers scaled up their efforts and achieved a significant milestone: producing the first cohorts of Potter’s angelfish capable of being distributed to aquariums around the globe—reducing demand for wild-caught specimens and promoting reef sustainability.

HPU Executive Director of the Oceanic Institute Shaun Moss, Ph.D., commended Glover’s work with the Finfish research program, saying, “Kent’s and Dr. Chad Callan’s recent publication is an important contribution to a growing body of knowledge about the life cycle of important coral reef fish and this publication will help advance important aquaculture and marine conservation efforts.”

Moss went on to say, “Kent’s journey highlights the importance of exposing bright, motivated students to real-world challenges and providing them with opportunities to participate in finding solutions to these challenges. There are a number of pathways for HPU students to work with the Oceanic Institute scientists to help solve technical barriers in the fields of marine conservation and food security.”

Kent Glover running in a Cross Country race.

Indeed, HPU’s commitment to applied learning shaped Glover’s undergraduate experience both in and out of the classroom. In addition to his volunteer research role, he was also deeply involved in student life and athletics—leading HPU Cross Country as Team Captain and winning multiple regional races, performing in the International Vocal Ensemble, and holding several leadership roles on the Student-Athlete Advisory Committee, including Treasurer and HPU’s representative at NCAA conferences across the country.

“My time at HPU was amazing,” Glover said. "HPU is really what you make of it, and I loved being able to connect with so many people, really getting to know my professors, some of whom I will be friends with for the rest of my life.”

The access to, and connections made with, faculty proved pivotal. “I started volunteering as quickly as I could. Everyone I know who’s successful in marine science was involved in something early, whether that’s at the Institute or through community efforts like Mālama Pūpūkea-Waimea,” he said.

Today, Glover cares for a broodstock population of 500-600 fish, ensuring they are healthy and spawning in captivity. While the team has temporarily reduced its work with Potter’s angelfish, their focus has shifted to other reef species.

“We’re trying to expand our repertoire of species that can be captive bred,” he explained. “Even though some data say the ornamental fishery in Hawaiʻi was sustainable, in my view, we should be making the least impact on the planet as possible.”

Living and working in Hawaiʻi has only deepened his commitment to sustainability. “Here you form a connection with the land and sea that you don’t find on the mainland,” Glover said. “Everything you do, you think about how to reduce waste, how to protect the environment. It’s a mindset shift.”

Looking ahead, Glover will begin a Ph.D. in Marine Biology at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa in the fall, continuing his work with Callan, who originally mentored him as an undergraduate. His research will focus on aquaculture development in Hawaiʻi, with an emphasis on culturally and ecologically significant endemic species.

“It’s difficult work—everything we do is labor-intensive and species-specific—but it’s rewarding. And it matters,” he said.

Moss agrees. “The Oceanic Institute’s Finfish Department cares and maintains a variety of marine fish species for the aquarium trade, as well as for human consumption. This team works at the nexus of marine conversation and food security to develop technologies to help solve global challenges. Kent’s contributions are especially noteworthy in the context of culturing marine ornamental fish for the global aquarium trade which is worth over a billion dollars annually.”

For Glover, it’s also a full-circle moment. “I go to work, take care of fish. I come home, I take care of fish,” he joked, referencing the aquariums he maintains at home, filled with fish he’s collected during freediving excursions. “This is my passion. It’s hard not to want to learn more.”